by Daniel HawkinsVIA:The Art of Not being GovernedSomething earth-shattering is about to happen.Tomorrow, the British-ruled country known as Scotland will vote for their independence.

The news has been focusing almost entirely on what this will mean for the UK and Europe. Most people have been completely preoccupied with what this will mean for the area economically. But that isn’t half the story; the trivialization of the matter should not be surprising. In all likelihood, if you’re an American reader, you probably hadn’t even heard of the Scottish independence referendum until the last week or two. But don’t be fooled; this is a momentous and historic event. This vote has the power to change the world forever. This may seem like a long-winded article, but I beg you to stay with it, and watch for the results of what may be the most important vote in history.

To understand why this is so important for you and why this could potentially transform the world as we know it, we have to learn the story behind it. To know why many Scots want to separate from England and the UK, we must first understand why these two countries are so different; we have to understand the history and nature of Great Britain.

First, some lessons in terminology are in order. If this seems elementary to you, I apologize, but most of us Americans are kept in ignorance by our media and schools, so this is important. The British Isles consist of: Ireland, Scotland, England,* the Isle of Man, Ireland, and many surrounding islands. The British government rules over all of the British Isles

except for the Republic of Ireland. What we call Great Britain consists of one island divided into three countries: England, Wales, and Scotland. This is the British mainland, stretching from Dover in the south to the Orkneys in the north. The United Kingdom, however, is a little different. The UK consists of: Great Britain (i.e., England, Scotland, and Wales), as well as the Isle of Man, Northern Ireland, and several other islands. While the Union Jack does not contain the Welsh flag, it basically integrates the countries of the UK into it:

This is their story:

This is their story:2,400 years ago, war and agricultural pressures forced the Celts to leave their homelands (modern-day France, Spain, and other parts of the European mainland). Sailing north, the Celts peopled the British Isles. From the Stone Age to the Iron Age, they dominated the area.** The marks of their rich and ancient history can be seen all over the Isles, from the Ring of Brodgar to Stonehenge, from the Meath Stone of Destiny to Castell Henllys.

Slowly, the Celts formed their own distinct sub-cultures and societies. The inhabitants of the large island to the west became known as the Irish. On the mainland known today as Great Britain, the Britons occupied the south. To the north lived the Picts, or the Scots as they were also called. The wild land on the west coast belonged to the Welsh. Over the centuries—due to some amount of luck and bloody struggle—remnants of these Celtic cultures have managed to survive in many parts of the British Isles.

Both the Romans and Greeks attempted to colonize the Isles, but to little avail. Upon hearing of its tempestuous sea and its wild people, the Romans were too afraid to enter Ireland. They tried and failed to tame the Welsh, and were repeated repelled by the fearsome Scots/Picts to the north. It seemed their domain would have to remain in the south. After much frustration, the Roman emperor Hadrian built a 73 mile-long stone wall between present-day Scotland and present-day England. For centuries, Hadrian’s Wall was considered the border between the wilder north and the more civilized south. This was only the beginning of the divide.

The Britons and the Romans lived together, sometimes in peace and other times in war. The Romans totally changed the cultural landscape, influencing everything on the British mainland, from law to art to religion, but the Britons still held fast to their heritage. Most historians consider their legacy to be the civilizing of the Britons. Ultimately, though, the land proved to be too distant and too wild compared to their homelands for the Greeks or the Romans to govern. As the Roman and Greek presence in Britain dwindled, another invasion began.

Driven by their own conflicts and agricultural pressures, three tribes from modern-day Germany sailed across the sea and into the British Isles. In the northernmost area of Germany, along the Danish border, came the Jutes. Just south of them came the Angles. From further south still came the most dominant tribe, the Saxons. Cousins to the Vikings who came later, these tribes brought with them a new religion, a new writing system, and a new language. They never quite made a strong impact in Ireland, Scotland, Cornwall, or Wales, however. Like the Greeks and Romans before them, these Germanic tribes were mostly restricted to the south. The Celtic lands proved again unconquerable.

Eventually, these three Germanic tribes became known as the Anglo-Saxons. Their new domain was called Angle-Land, or as we call it today, England. The Anglo-Saxon influence cannot be overstated. The English language owes its existence to the Anglo-Saxons (going back to the writing of Beowulf). We even borrow our days of the week from their religion: for example, Woden (their cognate of Odin) lends his name to Wednesday. As Christianity spread through Europe, it is believed by scholars that some Britons were Christianized earlier than the Anglo-Saxons, but that the Anglo-Saxons played a crucial role in establishing Catholicism as the first official religion of England.

By the 9th century AD, (after about 250 years of rule) not only was their culture unrecognizable, but the style of government in England was completely different than the Celtic lands outside it. While the Celts probably clung to

polycentric law and clan chieftains, the Anglo-Saxons created a mix of Germanic and Roman governing systems. What came out was a patchwork of earldoms, with written laws and legal monopolies. While language and religion easily crossed borders, the legal culture struggled to. These differences divided the Celts from the English, and enmity grew between them at every opportunity.

The Viking invasion had a considerable effect on life in the British Isles. These pagan pillagers had little mercy for what was, to them, a fertile land ripe for harvest. Unlike the Romans, they battled the Irish Celts for as long as they could. The threat to the English way of life was so great that the Anglo-Saxon earls united under a high king, establishing, for the very first time, the English Monarchy.***

The Vikings remained there for about 150 years, building permanent settlements in Ireland, Scotland, and most notably, eastern England. The area of England ruled by the Vikings became known as Danelaw. The remaining English lands—Wessex and part of Mercia—could be considered more civilized, but life was not easy for them. The English and Vikings were nearly constantly at war. Some Celts allied themselves with the Vikings in order to push the Anglo-Saxons out of their lands, but ultimately failed. The new English Monarchy claimed control of Wales and Cornwall, forming Britannia.

Danelaw finally fell—partly through war and partly through political alliances—toward the end of the Anglo-Saxon reign. The mark of the Vikings was left, but a new age was about to begin. After the death of King Edward the Confessor, several English earls vied for his throne. As England was weakened, a Norman nobleman by the name of William laid claim. The Normans, including Duke William, were descendants of Viking invaders, but were well integrated into French culture. With imperial ambitions and a name to make, William was about to change the face of the Britain forever.

William the Conqueror, Duke of Normandy and King of Great Britain

In 1066, following political scandals involving the Anglo-Saxon earls, William invaded in full force. The Anglo-Saxons fell, and their kingdom fell with it. What followed was a revolution in law and culture. But, we must know, it came at a terrible price. It was not enough for William the Conqueror to subjugate western England. He conquered what remained of Danelaw, as well as the earldoms surrounding Hadrian’s Wall. This was the Harrowing of the North. With a method of Total War, William starved, smoked, and rooted out the English and Celts wherever he could. Moving further north, his invasion of Scotland proved to be a bloody campaign, culminating in the temporary defeat of the Scottish monarchy and clans.

William’s attempts to quell the Welsh and the Irish did not prove as successful as his English campaign. However, even after his death, his imperial legacy carried on. Eventually, alliances were made and broken, and the Normans brought their hammer down on these Celtic lands. But the United Kingdom was yet to be born. There remained strong pockets of Celtic resistance in Scotland, Wales, and Ireland, and their respective monarchs and chieftains put up a fight for another few centuries. Future monarchs like Queen Elizabeth I would follow in William’s footsteps, laying claim to the whole of the British Isles.

In William’s time, however, he exercised iron-fisted control over what lands he could govern. Building upon the heavily Romanized legal system in England, he ordered a massive census to be taken of everyone in his kingdom. This tome became known as the Domesday Book. The event was such a defeat for the free peoples, our word “doom” (and Doomsday) as well as our connotation of “reckoning” come from this act. As a uniform tax code was imposed on his kingdom, William centralized the government in a way that hadn’t been seen since the Roman occupation. As monarch of Britain, William paved the way for even more bad blood between the English and the Celts.

William the Conqueror not only centralized and formalized the law, but also helped to establish the Feudal system. While Feudalism existed in one form or another in the rest of the British Isles, it took a particularly strong hold in England in the form of Manoralism (essentially an aristocratic plantation system). This system was far more codified than any semi-Feudal system in the past or in the Celtic lands. The various dukes, earls, and barons of England often held some influence in the king’s court.

To be an English feudal lord, however, it was usually a prerequisite that one had to have Norman ancestry, since the Normans were the conquering force. This class of British citizenry became known as Anglo-Normans. Beneath them were the un-assimilated Celts and Anglo-Saxons, who often toiled in the fields and were conscripted into wars in the name of their feudal lords. In many cases, the Scots were literally enslaved by the English. This was the Medieval Age in Britain. With its own parliament, court, and monarchy, that special mix of Brittonic, Roman, Anglo-Saxon, Viking, and Norman cultures became what we know today as England.

Scotland, among the other Celtic lands, grew up with its own history. With very little Roman influence, very little Anglo-Saxon influence, some Viking influence, and some Norman influence, the Celtic culture of Scotland remained quite dominant for centuries. While it isn’t as prominent as in Ireland or Wales, Scotch Gaelic is still spoken by 1.1% of the Scottish population. Throughout the Middle Ages and Early Modern Era, Scotland and England had a “love-hate relationship,” to say the least. Different Houses of Scotland had different attitudes toward the English nobility and monarchy. Sometimes, a Scottish monarch would simultaneously be the English monarch, and vice versa. Sometimes, they would be separate.

The history is complicated, to say the least. In any case, the Scots were never quite comfortable.

To say that the Scots were subject to foreign rule is both correct and incorrect, depending on whom you ask. The Unionist idea is generally that both countries exist on the same island, and the various intermarriages between the royal families forged a

de facto relationship that served as the basis for the formal union. But there has never been any consensus on this issue in Scotland. Repeatedly, English monarchs attempted to truly conquer Scotland, but largely failed. In the periods of English rule, bloody rebellions were always sure to come. One of the most notable early wars came in the form of the First War of Scottish Independence, pitting King Robert the Bruce and William Wallace against King Edward (“Hammer of the Scots”) I. If you’ve seen Braveheart, you should be a little familiar with this war. A period of independence followed****, but only for 18 years. Then followed the Second War of Independence, which lasted for about 25 years. Several rebellions were fought in the following centuries. As the English Reformation commenced, Scotland held onto Catholicism and also adopted Presbyterianism. This religious divide represented, and still represents, a massive divide between the cultures of the two nations. A true union between the two nations seemed impossible.

Robert the Bruce, King of Scotland. William Wallace and Robert the Bruce remain enormously important figures in Scotland.

A union did come, however. When Scottish monarchs held sway in England—particularly the Stuarts—the idea of a union was supported by most of the Scots. In 1603, the Scottish monarch James VI (James I in England) became the first monarch of Great Britain. This drove a wedge into Scotland between those who were satisfied with British rule (as long as it meant having a Scottish monarch to represent their interests), and those who believed that a union, no matter who was in charge, would be ultimately controlled by aristocrats. The divide remains there today.

For 100 years, the debate raged on, as did the English Civil War. However, the general idea (at least as phrased by the Unionists) was that it would be a Union of the Crowns. For the duration of the 17th century, both countries had separate parliaments. Both nations had their disputes with their respective governments, but they were, in fact, distinct. Eventually, the Scottish Stuart line was deposed forever. Still, many Scots believed having a Scottish parliament would act as a bulwark against disconnected, English interests (sound familiar?). But as the 18th century dawned, things changed.

On May 1, 1707, the Union of the Kingdom of Great Britain was formed. If you ask a Unionist, they will tell you that the Scottish parliament and English parliament unified into one parliament—the Parliament of Great Britain, centered in Westminster—consisting of both Scottish and English members to represent regional interests. If you ask a Scottish Nationalist, however, they will tell you that Scotland was utterly robbed of its sovereignty. The Scottish parliament did vote in favor of a Union, but as we libertarians know, it’s hard saying whether or not a parliament truly represents the wishes of its people. In either case, Scottish representation and sovereignty was formally handed over to England for the first and final time.

In the 1740s, a huge group of rebellious Scots—known as the Jacobites—attempted to throw off English rule.

This was one of the most significant Scottish Nationalist movements in history. Again, depending on whom you ask, their goals were either: to install a Stuart to the throne of the Union, or to install a Stuart to the Scottish throne and dissolve the Union. After a close fight, the Battle of Culloden signaled the defeat of the Jacobites. The English monarch (in this case the Anglo-German George II) would remain the monarch of Great Britain and the United Kingdom. The defeat was meant to be eternal. The Highland Clearances followed, sometimes with legal blows like the

Highland Dress Act and the

Disarming Act.

The bloody Battle of Culloden ushered in and solidified an era of Scotland’s ethno-cultural cleansing.

The 19th century was one of relatively absolute English rule. Expanding across the globe, the British Empire now had more than enough power to rule over most of its colonies. With Scotland as its neighbor, this proved to be relatively easy. A few skirmishes broke out here and there, but the Scots mostly deferred to the political process when they attempted to gain more independence. As the 20th century began, echoes of chaos came from the west.

The Irish War of Independence rocked the British Isles. The issue of Irish independence tore permanent rifts within the British and Irish citizenry. Ireland, much like Scotland, was once a Celtic nation, and had developed a completely different ethnic, religious, and cultural heritage from England. Their own wars of independence were fought, and their sovereignty was never taken quite as seriously as Scotland’s by the British government.

From 1918 into the ‘20s, the gravity of the Irish desire to break from England was felt by nearly everyone. This history warrants its own article, if not series of books, but to keep it brief: The northern Irish province of Ulster had long been inhabited by both an Irish Catholic underclass and Anglo-Irish Protestant “planters.” The Planters exercised much political and economic control over the area, extending down into Ireland.

Michael Collins, Irish politician and first leader of the IRA. He was ultimately assassinated.

Because so many people of British ancestry lived in Ulster, when the Anglo-Irish Treaty was finally signed in 1921, Ulster—which from then on was called Northern Ireland—opted out of the newly-formed Irish Free State in favor of joining the UK. The Irish Republican Army (IRA), which had fought for independence, was fragmented into two main groups: those who supported Northern Ireland’s loyalty to Britain, and those who wanted a united Ireland. Fueled by religious and political differences, the two sides formed their own paramilitary organizations and political parties. Violence over this issue lasted throughout the 20th century and into today. It was not contained to Northern Ireland, however, but spread across the water into Great Britain and the United States. While the violence has subsided, the divide remains.

The issue of Irish independence and the violent tenacity of the IRA lit a fire beneath the British government. With a large Catholic populace, many Scots were sympathetic to the Irish cause from the start. Others still (mostly Unionists) supported the Loyalist cause. Scots, for most of the 20th century, were not only preoccupied with being drafted into both World Wars, but generally were disinterested in armed resistance. Like Ulster, Scotland remained (and remains) divided on Unionism. Violence, for the most part, has been out of the question. With the formation of the Scottish National Party (the SNP) in the early half of the 20th century, Scotland gained significant political influence in Westminster. By the 1990s, Scotland regained its own parliament. Most people term this phenomenon “devolution” (you be the judge about what connotation that brings).

As Britain lost its colonies overseas, hopes for Scottish separatism grew. In the 1970s, upon discovering oil in the North Sea (in Scottish waters), many Scots—particularly Nationalists—supported the idea that the revenue from the oil should flow into Scotland. British Petroleum (BP), formerly the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, immediately focused on obtaining North Sea oil. Norway obtained much of the oil, but many Scots viewed the oil as belonging not to Britain as a whole, but to Scotland. With billions of barrels of oil at stake, it’s no wonder that

BP is urging Scotland to stay in the Union. The financial concerns of England (well, more accurately,

English Corporatists) are taking center-stage. The

English aristocrats and bureaucrats are begging Scotland to stay in the Union. The attitude of many of those in the “Better Together” campaign can be called, at times,

condescending. The shackles of empire are quaking under the strength of the Scottish spirit of liberty.

More importantly, the breaking up not only of the United Kingdom but of Great Britain itself means that large governments,

maybe the State itself, could lose power at any moment. It’s no surprise to anyone that the idea of secession is gaining legitimacy around the world. Kurdish secession, Ukrainian/Russian secession, Venetian secession, Texan secession, the successful South Sudanese secession—even the

corporatist propaganda outlets are taking notice. The question posed by these movements is: “If Scotland can successfully break away after 1,000 years of attempted and successful English rule, why can’t we?”

That’s the question of the century. That’s what it all comes down to. One of the many definitions of “nation” (and the one I favor) is: “an aggregation of persons of the same ethnic family, often speaking the same language or cognate languages.” (

http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/nation).By this definition, and by the measure of History, these are two separate nations. Here’s a more important point:

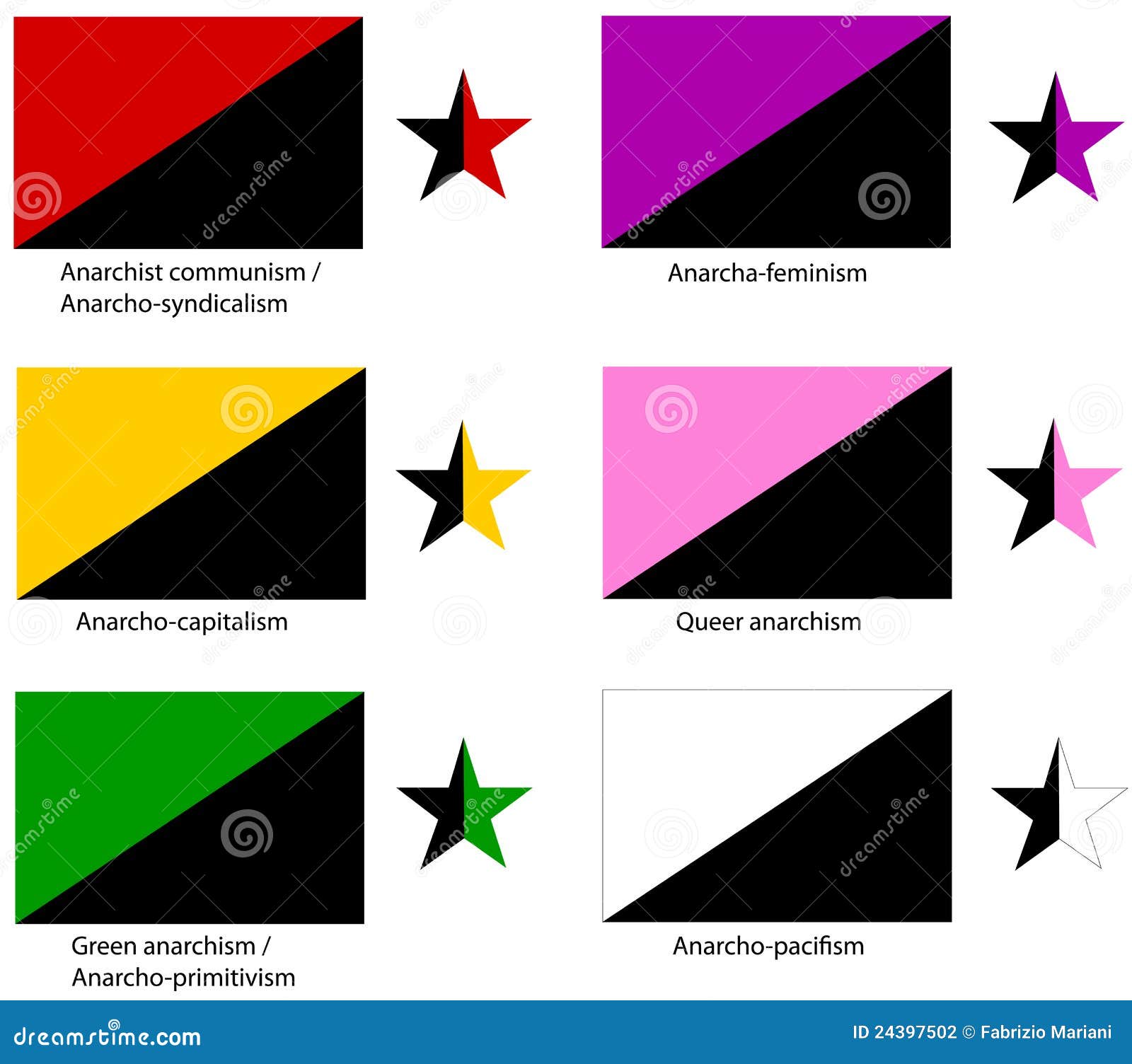

Any human being—regardless of origin, regardless of reason, regardless of political position—deserves to be free. They deserve to make their own destiny. Many conservatives, libertarians, and even some anarchists have been criticizing Scottish independence as silly. Their new government, and the SNP in general, may turn Scotland in to a socialist nation in the style of Sweden or Denmark. This is true. Most Scottish Nationalists lean fairly hard to the Left. But that doesn’t always have to be the case. Who knows what will happen to Scotland in the future. Even if it is the case, why does it matter? It’s not my country. They are their own people, each individual Scot is his or her own person. It’s not my place nor is it my desire to tell them what to do.

Whether or not Scotland can be economically viable is a matter of debate, but everyone should note that the same country that churned out world-renowned shakers like Adam Smith and James Watt has a historical foundation to stand on when it comes to economics.

Many Scots want to be free. They’re tired of the English yoke. They’re tired of being subjects of the Queen and Prime Minister.

They’re tired of getting pushed into Britain and America’s costly wars, and tired of sacrificing their freedom in the process. They want to trade with who they choose to trade with. They want to break away and form their own destiny. As Lysander Spooner said about the American Civil War:

“The question of treason is distinct from that of slavery; and is the same that it would have been, if free States, instead of slave States, had seceded. On the part of the North, the war was carried on, not to liberate the slaves, but by a government that had always perverted and violated the Constitution, to keep the slaves in bondage; and was still willing to do so, if the slaveholders could thereby induced to stay in the Union. The principle, on which the war was waged by the North, was simply this: That men may rightfully be compelled to submit to, and support, a government that they do not want; and that resistance, on their part, makes them traitors and criminals.”Secession is a dangerous idea. The failure of secession movements or any rebellion can inspire two things: a renewed faith in large, imperial governments, or a loss of faith in government in general. In my opinion as an anarchist, I am not always disheartened when revolutions fail. The political process, after all, is fundamentally opposed to liberty. If secession movements win, the results are obvious. If this referendum passes, it could mean that the concept of empire, that the concept of government, is in its death throes. As the “libertarian moment” approaches, this could mean the dawning of an era of real, honest freedom. Yes, secession could mean that Scotland could fall under another corrupt government, and yes, I believe that

all government is slavery. I’m not a Minarchist. The key difference here, and the reason why I as an anarchist support this movement, is because this is a step toward the right direction. I don’t want the Scots to stop at national independence. I want them only to pass through and go on to better things. I don’t want Scottish Nationalism; I want Scottish Separatism. I want

real independence for each and every Scot, for each and every human.

“Once one concedes that a single world government is not necessary, then where does one logically stop at the permissibility of separate states? If Canada and the United States can be separate nations without being denounced as in a state of impermissible ‘anarchy’, why may not the South secede from the United States? New York State from the Union? New York City from the state? Why may not Manhattan secede? Each neighbourhood? Each block? Each house? Each person?”–Murray Rothbard

“Once one concedes that a single world government is not necessary, then where does one logically stop at the permissibility of separate states? If Canada and the United States can be separate nations without being denounced as in a state of impermissible ‘anarchy’, why may not the South secede from the United States? New York State from the Union? New York City from the state? Why may not Manhattan secede? Each neighbourhood? Each block? Each house? Each person?”–Murray RothbardSoar Alba gu bràth

Footnotes:*Whether Cornwall should be considered part of England is its own issue. A heavily Celtic area, Cornwall has its own unique history and culture, along with a thriving independence movement of its own.

**A large portion of historians term this area of Europe “Gaul” (the name the Romans gave it), and so term the Celts who moved away “Gaels.” We call their language/culture Gaelic. There are subtleties and debates about this terminology, however.

***It was around this time that Scotland came under a monarch. However, it remained a Scottish monarch for centuries, and most monarchs had considerably weaker control over the clans when compared with the English system of governance. Even after the Norman invasion, Scotland (due to its distance and its distinct culture) was difficult to pull under their yoke.

****While Edward ultimately failed to unite the kingdoms under his rule, he did succeed in taking the Stone of Scone as a spoil of war. The Stone of Scone (also called the Stone of Destiny) was symbolically used as the coronation rock for the high kings of Scotland, and remains an important cultural icon. The Stone was placed under the Coronation Chair in Westminster Abbey, where it remained for centuries. In 1950, some Scottish Nationalist students attempted to steal the Stone and return it to Scotland; however, the British police returned it. In the 1990s, in a symbol of amicable union and apology for past offences, the stone was returned to Edinburgh.